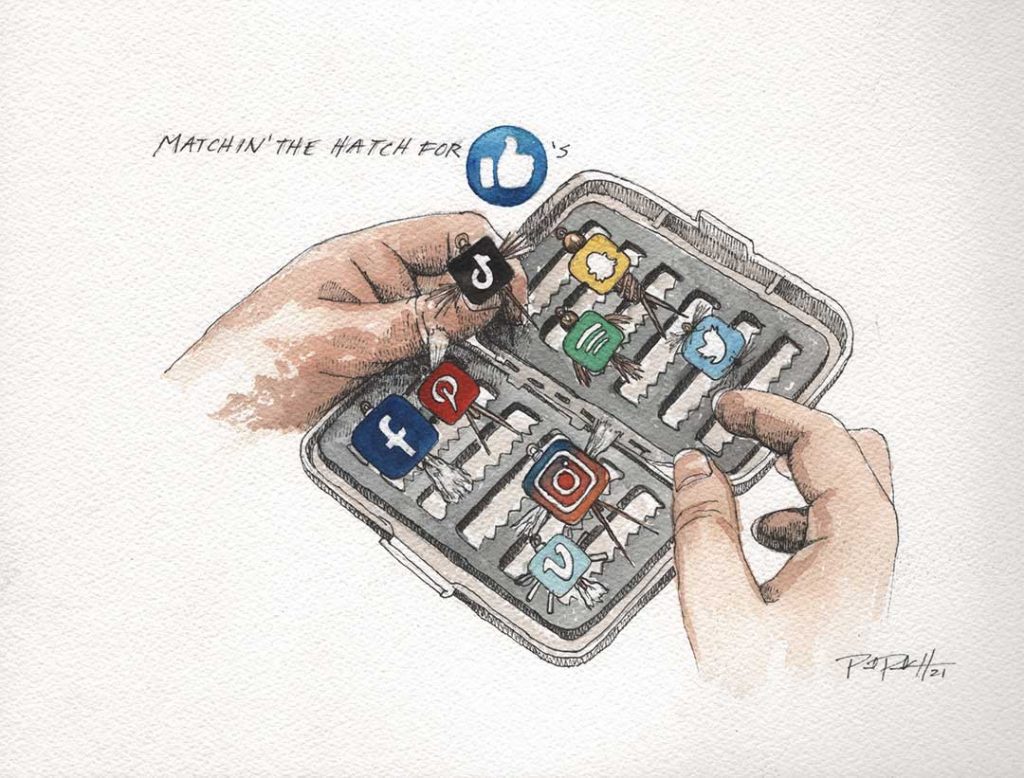

Illustration by Paul Puckett

By John Dietsch

I just landed this beautiful 21-inch brown trout and my hands rattle like a rusty air conditioner. I hold the brightly colored fish in the water then, knowing better, raise it up to the ubiquitous camera lens.

“Where’s the camera?” I ask my buddy PeePaw. His hands are empty.

“No photos today,” he says. “We’re getting phober.”

“You’re joking right?”

He doesn’t respond.

“But I’ll only share it with my friends.”

“All FIVE THOUSAND of them?”

After a brief but sharp exchange that threatens our 35-year friendship, I reluctantly release my unphotographed fish to the water. Distraught, I look up and see all that I missed during my section of float, stripping my streamer and playing the fish… without looking up… not once. I just stand there for a moment and marvel at the vastness of the river, sky and mountains folding into God light.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” PeePaw says, noticing my shame-filled gaze as we look out at the western expanse. “We’re starting to forget what this is all about.”

Grumpy PeePaw, a veteran angler who started guiding with me in the early 1980s (he quit three decades ago), believes that the Internet, and influencers in particular, have transformed fly fishing into something we can hardly recognize. He is not alone.

“This new generation of anglers, they just don’t seem to have the same sort of respect for the sport that we had to have growing up in order to make a name for ourselves,” says veteran angler Dave McCoy, age 51, owner and head guide for Emerald Water Anglers. With nearly 11,000 followers on Instagram (or 11K on Insta as my kids would call it), McCoy is a respected brand ambassador in the industry.

“Somehow everyone (in this new generation) is born a pro and then there is that cliche of free gear is the best gear,” he says. “Every manufacturer would rather give a young “influencer” -–a term I cannot stand––free gear in hopes of showing it favorably on their feed. They are acting pro but being a far cry from it.” Then he says, with a smirk: “Think I just threw up in my mouth a bit.”

The term influencers may seem new, and while the word itself was only officially introduced into the English language in 2019, the concept of an influencer market giving birth to a new breed of endorsed celebrities can be traced back thousands of years to the Roman Empire when Gladiators were paid to promote the armor and weapons they donned for battle.

I don’t think Dave really chundered, but maybe he’d put too much Cholula on his fish tacos.

In the influencer game it is all about how many followers you have on social media, the image you project online and not necessarily your fishing acumen.

“I think in the fly-fishing industry an influencer can be defined as someone who leverages their time in the outdoors to promote brands,” says April Vokey, one of the industry’s first influencers.

The term influencers may seem new, and while the word itself was only officially introduced into the English language in 2019, the concept of an influencer market giving birth to a new breed of endorsed celebrities can be traced back thousands of years to the Roman Empire when Gladiators were paid to promote the armor and weapons they donned for battle. While you might think that Sir Izaak Walton, who first published The Compleat Angler in 1653, was fly fishing’s first influencer, you would be mistaken. Dame Juliana Berners, a.k.a. the “Fly-Fishing Nun,” presumably became the first known influencer to discover, write about and promote the joys of fly fishing more than a century before Walton.

Women now represent nearly one-third of all fly fishers and it is no secret that brands are targeting them as the fastest growing segment in the industry. However the leverage that women began wielding in sports marketing around the turn of this century has also become a gamechanger in the niche of fly fishing.

“Tennis player Anna Kournikova (1.7m Insta), in the late 90s, became more valuable as an influencer than as an athlete,” says Peter Suciu (137 Insta) who writes about social media for publications like Forbes. “Guys who didn’t necessarily care about tennis liked seeing Kournikova more on the screen than on the court.” Kournikova, who never won a major singles title, made nearly three times more in endorsements than prize money “making her total earnings much higher than women who were much better tennis players.” Nonetheless her popularity helped grow the sport, if not rile her rivals.

And here is the catch. “Influencers have become so big that they can become bigger than the brands they are endorsing,” says Suciu.

In 2018, Kylie Jenner (223M Insta) tweeted one sentence about her not using Snapchat anymore and the next day Snapchat’s stock dropped $1.3 billion. That is billion with a “B.” How might a powerful influencer affect a major brand like Patagonia or Orvis by publicly rejecting a line of its products in the near future?

Think Joan Wulff on steroids. Case in point: April Vokey already has nearly three times the reach of icon Flip Pallot and more than twice the followers than Winston Rod Company (58.3 Insta), not to mention other established brands.

First known as a respected BC Steelhead guide starting in her late teens, Vokey became one of the first influencers in the fly fishing industry. She later left the guiding profession around 15 years ago to fish and focus on the prized trifecta in social media: becoming an influencer, brand ambassador and content creator. She estimates that her biggest money maker is generating content like videos, films, articles, presentations, online classes and blogs. She now has over 125K followers on Instagram, perhaps the most followers of anyone in fly fishing.

When it comes to differentiating between an influencer and brand ambassador, she goes on to explain that a brand ambassador reps brands endemic to (i.e. inside) the industry and an influencer typically promotes non-endemic ones outside the industry. In her opinion, the big difference between a brand ambassador and an influencer is that the latter is more likely to promote a product they don’t use or like just to make money.

Either way, both endemic and non-endemic brands sometimes give away product, fees or both to mediocre anglers with large followings, bolstering the perception that brands are contributing to the increased commoditization of a sport that has traditionally eschewed commercialization.

“I think that influencers are given a bad rap in a lot of ways,” she says.

At age 37, Vokey sees herself as a kind of influencer of influencers when it comes to other younger women like Maddie Brenneman, 30 (108K Insta followers), and Shyanne Orvis, 24 (46K Insta followers), who have had to endure constant criticism from online haters who claim that these young women have no right to be so popular at such a young age, especially being women with so little on-the-water experience. Yet each of them has managed to partner, as Vokey has, with many brands outside of the industry in markets like automotive, alcohol, eyewear, storage, pharmaceutical and cannabidiol (CBD) oil, as well as many others. Each of them swears that they love and use all the products with whom they are partnered. Another issue with this is influencers who integrate a product into their feed without including the hashtag, #ad, an unenforced requirement by law. This kind of deceitful practice of user-duping just adds to false accusations that all influencers lack integrity and transparency. Still, detractors call foul.

In the case of Vokey, she certainly had credentials as a BC Steelhead guide when she started posting around 15 years ago, but she still got backlash. For Shyanne and Maddie their backgrounds appear to be more controversial. In the case of these young women, each have four and six years of guiding experience respectively, mostly on private water or at private clubs. Yet they are already partnering with big name brands––gigs that piss off a lot of people claiming that influencers like Brenneman misrepresent their expertise and that their technique is underdeveloped.

Last time I checked, Maxine McCormick became the 2016 World Champion fly caster when she was only twelve years old, so young females kicking ass is nothing new. Problem is Maxine’s achievements were measured by judges, but the yardstick on Insta followers is vague and leads to antagonism.

“Arbiters of the rules and ethics in a sport spend so much time worrying what is and isn’t fly fishing and who deserves recognition and who doesn’t,” says Marshall Cutchin (292 Insta followers), publisher of the popular online fly fishing journal Midcurrent (22K Insta followers). “They could be spending all that time, celebrating the sport and showing us how to take better care of the world around us.”

“Who is saying you have to meet all these standards in these categories?” Shyanne asks while flipping the bird in reference to what she calls “an industry of white old men” and their resistance to change.

“All of our journeys are different so why do we have to fit this mold and who’s setting the precedent for what you need to be, like who is setting the rules?”

“Shyanne can fish,” says Vokey. But she also says there are definitely “nice people” who can’t fish but who milk their followers, fake fish shots and run a racket more for financial reasons as opposed to passion (she named one woman in particular she suspected of this, but wanted her to remain anonymous). On the other hand, “Shyanne has good intentions, but she still gets bullied.”

Having grown up in foster homes, Shyanne left her hometown of Flint Michigan as a teenager and drove to Colorado where she fell in love with fly fishing. “At the beginning posting was personal,” she says, “like hey if you don’t want to be stuck in a small town, get into the outdoors… If I can do it you can do it.” It would seem that her aspirational journey touched a chord with followers because she attracted brands that allowed her to expand her platform.

“I didn’t set out to do this,” she says, referring to all the visibility she gets traveling around doing photo shoots and representing brands. “I just love to fish and to be a fish bum. But it is not what people think; it’s tough to make a living.”

To make ends meet she now works two or three other jobs in addition to guiding. “People think I make a lot of money but I still live in a shed with two outlets in someone’s backyard, and when my friends go out I pretty much stay in working on my social media stuff,” she says.

But in the end, she says it’s worth it. “My platform can be a catalyst for change,” she says as she prepares for a Smith Optics photoshoot in the Florida Keys. “I want to inspire and encourage, to spread positivity, to attract new anglers to the sport of fly fishing —and to protect our resources.”

Considering that three million more fishing licenses were sold this year compared to last, at least some of that growth can be attributed to influencers. However, the debate over the caliber of influencers continues to bleed into the fabric of the sport, especially when it comes to never-ever anglers entering the sport for the first time.

“We have to be careful as an industry not to create an “elitist bubble” by setting the bar too high for people coming into fly fishing,” says Cutchin.

On the other hand, says McCoy, “I spend SO much time trying to regain trust for the industry with new anglers after they have had poor experiences with people who are considered an influencer but don’t know how to fish or guide.”

Then there’s the generational question.

“Many of the most deserving anglers are being totally neglected in the social media game,” says Vokey. “They’re tossed aside for somebody younger who’s got a large media following solely because they take nice photos and know how to use social media ––it’s asinine and offensive.”

“The people who really deserve to have the street cred often don’t have a social media presence,” says Cutchin. “That’s because some of them don’t want it and some don’t know how to get it.”

Either way, both endemic and non-endemic brands sometimes give away product, fees or both to mediocre anglers with large followings, bolstering the perception that brands are contributing to the increased commoditization of a sport that has traditionally eschewed commercialization.

According to McCoy, “Nearly all fly-fishing industry executives are guilty of putting entirely under-experienced personas on their feeds as experts because they have a lot of followers.”

And therein lies the rub. The temptation to back a young personality new to the industry with a lot of followers, but little experience, is tempting for many brands who have struggled to find a return on digital marketing.

“It is frustrating for (brands) who work really hard to build engagement but feel like it is not paying for itself nor worth its while,” says Cutchin. “They become very interested in this younger market coming in because they know how it all works. It’s a much easier way to get recognized in the marketplace.”

Studies have shown that consumers are more apt to be interested in purchasing gear that is integrated into real life scenarios than seeing it in advertisements.

One problem seems to be that some in the old guard, to a greater or lesser extent, is becoming increasingly reluctant to hand off the torch to twenty-somethings in an industry known for its nonagenarian legends like Lefty Kreh and Joan Wulff. The result is a new generation of women influencers who are often attacked and vilified by online trolls, who, like their folklore counterparts, ambush and aggressively attack influencers and other users online whether they deserve it or not.

“The other day I was sent a link to a new page and there was this pic of me,” says Shyanne. “But instead of me holding that nice brown I remembered, the fish had been photoshopped out so I am now holding something phallic painted like a brown trout. There are all these other nasty things I don’t even really want to talk about.” The post was soon removed but the damage done.

“It’s awful. It’s terrible” says Simon Gawesworth, RIO Products Brand Manager (who was surprised to learn that he had an Insta account apparently created by someone else). “I am not surprised at this behavior because the industry is full of jealous people and wannabes who want that kind of attention but don’t get it.’ He thinks highly of Shyanne and all she does for charity and education within the sport.

Shyanne is not alone in facing so much criticism.

“I learned a long time ago that it doesn’t help or make you feel good to engage with negativity,” says Brenneman, who is fast becoming the new face of fly fishing with one of the largest online following in the sport. She partners with Lululemon, YETI, Backcountry, CBDistillery, Buff USA, Thule, Cutwater Spirits & Revant Optics and according to Most Popular Celebrities’ Net Worth on FamousIntros.com, makes somewhere between $100K and $5 million a year.

“I have never claimed to be the best angler in the world,” she says. I have been upfront about my experience because I don’t think there is anything wrong with it.”

So why the intimidation? Aside from jealousy and unwarranted sexism, some people accuse unethical influencers of buying fake followers, hiring click farms and promoting products that they are being paid to use and don’t like. When an angler/user begins to doubt what these black hat influencers are saying, they always have the opportunity to unfollow those people. However there are those who take it a step further.

Enter the trolls. So-called anonymous troll accounts like Copper Plated Sixes have popped up over the years taking a hard line against what they perceive as an affront to traditional hunting and fishing practices. Many of these troll accounts see themselves as a kind of social media police for the outdoors, collecting posts and flagging influencers they label as fake and others who they accuse of pimping out or disrespecting field sports.

On the other side, many claim these types of vigilante consortiums, hiding behind aliases or anonymity, are a cowardly means of attacking people who don’t deserve it. CPS believes it serves a purpose by educating its followers on what they should or shouldn’t post, as well as flagging influencers who they believe are inauthentic, but the question is at what point does this sort of vigilante behavior become nothing more than bullying?

For years CPS had Shyanne in their sights, and it wasn’t until Vokey reminded them, on one of her podcasts, what it was like for her when she was Shyanne’s age, did they stop publicly slighting her. Still to this day, no one from Copper Plated Sixes has ever publicly divulged their names.

“I already have this label at 24 like there’s no going back now,” says Orvis. In fact, the bullying got so bad that she still finds it challenging to attract endemic sponsors. “I can’t get any fly fishing brands to want to work with me and why is that my fault? Because you’re relatively new and you’re 24 years old? What, I am I supposed to wait until I’m 40?”

The good news for Shyanne is that most of the people I talked to in the industry seem to understand that she got a bad rap, but what about those who need to be reined in for their fraudulent behavior? The jury is still out.

For the kind of scrutiny going on in the social media world to police influencers, the qualities of patience and perseverance learned from fly fishing are de riguer for brands and online personalities who combine good intentions and transparency.

One of the solutions brands are now adopting in fly fishing and other industries is the concept of backing micro-influencers with less following but whom they know better. Rather than banking on one major influencer with 100,000 followers, they might spread out their budget over, say, ten influencers with 10,000 followers.

“We’re looking for people that embody a certain quiet confidence,” says Simms CEO Casey Sheahan (1.2K followers on Insta). “Both in their fly fishing and their dedication to conservation efforts as well as their ability to bring other people along in the sport in a thoughtful and considerate way.”

“Fly fishing is supposed to be a sport where we really pride ourselves on being totally noncompetitive and totally in sync with nature. And a big part of that is participating in protecting the resource,” says Vokey. “The second those intentions are compromised it immediately triggers a level of hostility.”

Including the number of someone’s Instagram followers when talking about who they are is meant to be irritating, and reminds me of anglers who count their fish (not that I am judging or anything). Of course, fly fishing is not about follower rankings; it is about being on the water rather than your device.

As Casey Sheahan puts it, “fishing is like a metaphor for life. It’s just another way that we express ourselves and it is symbolic of how we show up in life.”

In the old days I used to say that I never met a fly fisherman I didn’t like, but once I started showing up in the media, I realized that there were people who didn’t seem to like me. And I think that’s a shame.

Back on the river, PeePaw and I stand there in silent appreciation of the view and melodic sound of the river I had momentarily forgotten to honor.

“It’s enough being on the river like this,” I say.

Our silence is suddenly broken. I hear the sound of a huge splash and shouting.

“Hey Mark, answer the phone!” A vested angler on the first boat yells to his friend in another. Each holds up a live foot-long trout to their ear as they pretend to have a phone conversation using the fish as faux devices.

“Hello,” Mark says laughing.

“Are we really witnessing this?” I whisper to PeePaw who is speechless.

Mark’s buddy, standing tall in the middle of five boats, shouts on the fish, “Hey Mark Fly Fishing Executive this is Steve. Give me more fishing gear brother! Just caught a fifteen pound farm-fed fatty,” Steve says, holding the trout-phone to his ear while hoisting the grotesque and bloated rainbow in the air. Nine other “anglers” snap photos before they disappear around the corner.

PeePaw puts his head down, searching for the words… And then it comes to me.

“An Influencer Rows Through It,” I say.

“I think I just threw up in my mouth.”

John Dietsch is best known for overseeing the fly fishing scenes in the film A River Runs Through It. He is an award-winning author and filmmaker and Aspen Colorado guide (starting in 1984) as well as a defunct fly-fishing social media pioneer (Hook.tv). He is the producer/host of the TV series Adventure Guides: Fishing Edition, dozens of other successful fly-fishing media projects, and author of a new book: Graced by Waters that expands on the theme of Norman Maclean’s novella by exploring our connection to waters and their ability to heal us in the face of loss. He considers himself an influencer (Insta 583) of fish!

John Dietsch is best known for overseeing the fly fishing scenes in the film A River Runs Through It. He is an award-winning author and filmmaker and Aspen Colorado guide (starting in 1984) as well as a defunct fly-fishing social media pioneer (Hook.tv). He is the producer/host of the TV series Adventure Guides: Fishing Edition, dozens of other successful fly-fishing media projects, and author of a new book: Graced by Waters that expands on the theme of Norman Maclean’s novella by exploring our connection to waters and their ability to heal us in the face of loss. He considers himself an influencer (Insta 583) of fish!

GracedbyWaters.com.

Instagram.com/dietschjohn

Johndietsch@gmail.com

5 Comments

This was, without question, the very best discussion I have ever seen or heard on “influencers” whether fly fishing related or not. I have been working hard on a website for over a year that is my way of “paying it forward” for the more than 40 years of pleasure fly fishing has given me. My two primary purposes for the website and social media presence is to (1) help educate the “newbies” to fly fishing and (22) promote conservation efforts primarily directed at our cold water resources.

I am doing a complete rebuild of the existing site with the intention of getting other fly fishers like me to contribute their knowledge and experience . Many of us are aware of the things you discuss and are saddened and often disgusted.

I belong to many social media groups and constantly see the issues you discuss. I am good friends with many like Mike Lawson, Rene Harrop and others who have backed away from social media engagement for the reasons you described here. It is a shame…

Very good work!

Jerry Denson

onlyonflies.com

Hey Jerry,

Thanks for the accolades. Writing this article was arduous but worthwhile as it has sparked the kind of conversations that are needed. I look forward to checking out your site; it sounds like you are offering the kind of content and attitude I wish were shared with every outfitter and brand in the industry. I am hoping that there will be a resurgence that focuses on education and conservation rather than just catch and reinvest (in gear and the like). I am working on my website as well with a focus on offering content, trips and retreats that are more about the spiritual and wellness essence of the sport (based on my new book Graced by Waters), similar to the many offerings out there for people with PTSD or cancer but geared for all of us, especially in these difficult times of loss.

Monetization always sucks the magic out of everything.

.. & plaid shirts.

Thanks for the apt synopsis of my article Frank. My buddy PeePaw says he keeps the throw up in his mouth so it won’t stain his plaid shirt! JD

Fly fishing isn’t a traditional sport of competition – football, basketball etc. Yes, there is competitive fly fishing but it’s small and even people that have been fly fishing for a lifetime couldn’t give you the name of someone on the USA fly fishing team. Fly fishing is a learned craft in which only experience brings forth the lessons needed to be better at this sport/hobby/passion. While I have an instagram account, it’s mainly used to communicate with people that are like minded and to help share information about certain things related to fishing. Social media is a lot like TV. It’s an escape and unfortunately, there’s a large number of people that are posting highly stylized photos that are misrepresentations of their experience, their knowledge and their skill level. It’s a shame that companies like Winston don’t have the followers that some of these “influencers” have. But in my mind, these companies reputations are built from creating products by people that are the “real deal”. Advertising is necessary to every business that’s trying to sell a product. It’s up to the consumer to decide whether their advertising aligns with the quality of the product being sold and the ethos that that particular company is trying to adhere to.